This blog post provides a simpler account of a scholarly essay by Noel Weeks called, “The Bible and the ‘Universal’ Ancient World: A Critique of John Walton,” Westminster Theological Journal 78 (2016): 1–28.

But first an introduction.

The titles of several of John Walton’s books make clear his view that the Bible comes from an ancient world that we no longer understand . . . unless we accept Walton’s explanations of how these ancient cultures worked and thought, and then apply Walton’s reconstruction to re-intrepret the Old Testament.

Apparently the books are selling well, for IVP has turned this into a “Lost World” series with one more volume per year, for 2017, 2018, and 2019. In every case the premise of the volume is that Western readings of the Old Testament have grossly misunderstood the meaning of the text by ignoring the Ancient Near Eastern context. For example, The Lost World of the Torah (i.e., of Gen–Deut), due to come out in Feb 2019, argues that “The Ancient Israelites Would Not Have Understood the Torah as Providing Divine Moral Instruction,” and “We Cannot Gain Moral Knowledge or Build a System of Ethics Based on Reading the Torah in Context and Deriving Principles from It” (the book’s theses have been announced online). Presumably the Ten Commandments, part of the Torah, do not provide moral instruction? We shall find out when the book is published.

As with all of Walton’s books, this raises questions about how much we can assume that there was such a thing as an Ancient Near Eastern mindset that was shared across very diverse cultures and several millennia. Weeks’s article from 2010 pointed out enormous problems with this assumption (we reviewed this in a previous blog post).

Enter a second essay by Weeks, directly challenging Walton.

Weeks begins by pointing out that the crucial weakness in Walton’s method is the belief that the ancient world and our modern world are so vastly different that the Bible’s conformity to thought patterns of the ancient world—as reconstructed by Walton, we hasten to add—and its differences from our world, can be taken for granted. As a result of this assumption, Walton doesn’t need to make careful distinctions in his evidence from the ancient world. Weeks, however, shows how important it is to evaluate the evidence much more closely than Walton does.

First, he points out biases in the textual evidence (mostly clay tablets) from Mesopotamia, that is, the land of the Sumerians, Babylonians, and Assyrians:

- 100s of 1000s of Mesopotamian texts versus a few dozen from Israel (besides OT)

- 90% of Mesopotamian texts are economic or administrative records but the biblical text of the OT is not of that sort

- the 10% of the Mesopotamian texts remaining are mostly for divination & exorcism

- next, it’s unclear whether the few Mesopotamian texts that could compare to the Old Testament represent matters central to Mesopotamian thought

- also unclear whether Mesopotamian scribes recorded views of their own culture & time or simply repeated past stories for other reasons

- further unknown whether the average person in Mesopotamia thought in the way of these few texts or whether such views belonged only to the elite

Weeks concludes, “When all these reservation and qualifications are taken into consideration, the simple quoting of a Mesopotamian text as the background to the OT is implausible” (6).

Weeks next reviews the evidence from Egypt, then from Hittite sources, and then from the Transjordan area. The only site that provides texts of ancient myths is Ugarit, on the Syrian coast (7). But Ugarit has no creation account, nor do the Hittite myths (8). The only creation account, from the Enuma elish, is actually about the superiority of the Babylonian god Marduk. The dating of the document’s origin is likely late second millennium B.C., too late to have been consulted by Moses (9).

Weeks asks whether even ten references over two thousand years and two cultures can establish a common view, and then adds that “on some crucial points Walton is more likely to have two than ten” (10).

Walton’s key arguments next receive scrutiny.

- First, about creation in Genesis not being about the origin of things, but only their functions, Weeks provides two counter examples from Babylonia (11).

- Second, the particular functions that Walton ascribes to each day of creation are rather out of line with his claim to convey the ancient mindset, for he chooses very abstract functions, such as time, the architectural design of cosmic geography, fecundity, etc. (12).

- Third, the idea of creation as temple where God came to rest just like all other ancient gods lived in temples is challenged by the fact that these gods were often described as living in other gods’ temples or even reposing outside a temple, and especially, having their more permanent residence in a heaven (13–14, 18).

- Fourth, the assumed “scientific naiveté of the ancient people in apparently thinking of the universe as a three-tiered structure is false. While such texts exist, other, different texts from the same cultures also exist (14–17).

- Fifth, the importance of the seven-day period in general does not need to be questioned, but its purported tie to the length of time for building a temple fails (19).

Interestingly, Weeks concludes that Walton has not only made the Bible more like the surrounding cultures, but he has also made the surrounding cultures more like the Bible (18). And, we might add, both as unlike today as possible.

In a major section of his paper, Weeks also critiques Walton’s application of his method to Scripture more broadly, but for our purposes we will not describe this (21–6).

He concludes,

In summary I am not impressed by the whole approach outlined here. There is no recognition of the difficulty of discerning a uniform mind of the ANE. Individual extra-biblical texts are turned into representations of the whole huge chronological and cultural span. Even more striking are claims that are simply false (26, bold here and in following paragraphs added).

The tendency of [Walton & Sandy’s] system is to push any real impact of God on the world further into a grey area . . . They reject Deism . . . but their system has the same tendency . . . The points of interaction between the deity and the physical world are postulates of faith without tangible physical evidence. [However], the biblical text is clear that when God interacts with the physical, the physical world is actually, visibly changed (26).

Structurally this approach is very similar to the neo-orthodox thesis of a Word of God within the Scriptures but not synonymous with the Scriptures (27).

In other words they make no attempt to set forward a method by means of which we might climb out of the language of an ancient time into the message for us. I suspect that they do not tell us because they already know what parts of the text are objectionable. Whether is it the parts that do not fit Kantianism or the parts that make the modern unbeliever scoff, it is modern problems that really drive them. I fear they have fallen into the trap they wished to avoid (27).

We need to see that the Bible stands over against both the ancient world and the modern world. It does so because God is distinct from the creation he made and yet he impacts upon it (28).

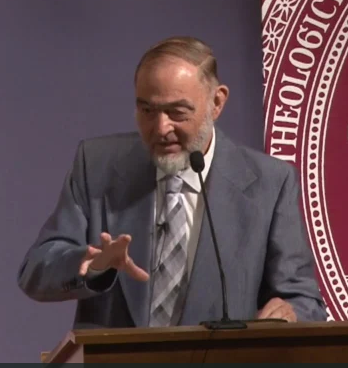

For those who prefer to get the gist of this article in video format, you can watch Weeks’s lecture at Westminster Theological Seminary, posted online. I’m sure they’ll be happy for the added web traffic 🙂 and you will be happy to listen to his very winsome style of lecturing. A pdf of the article can also be obtained.